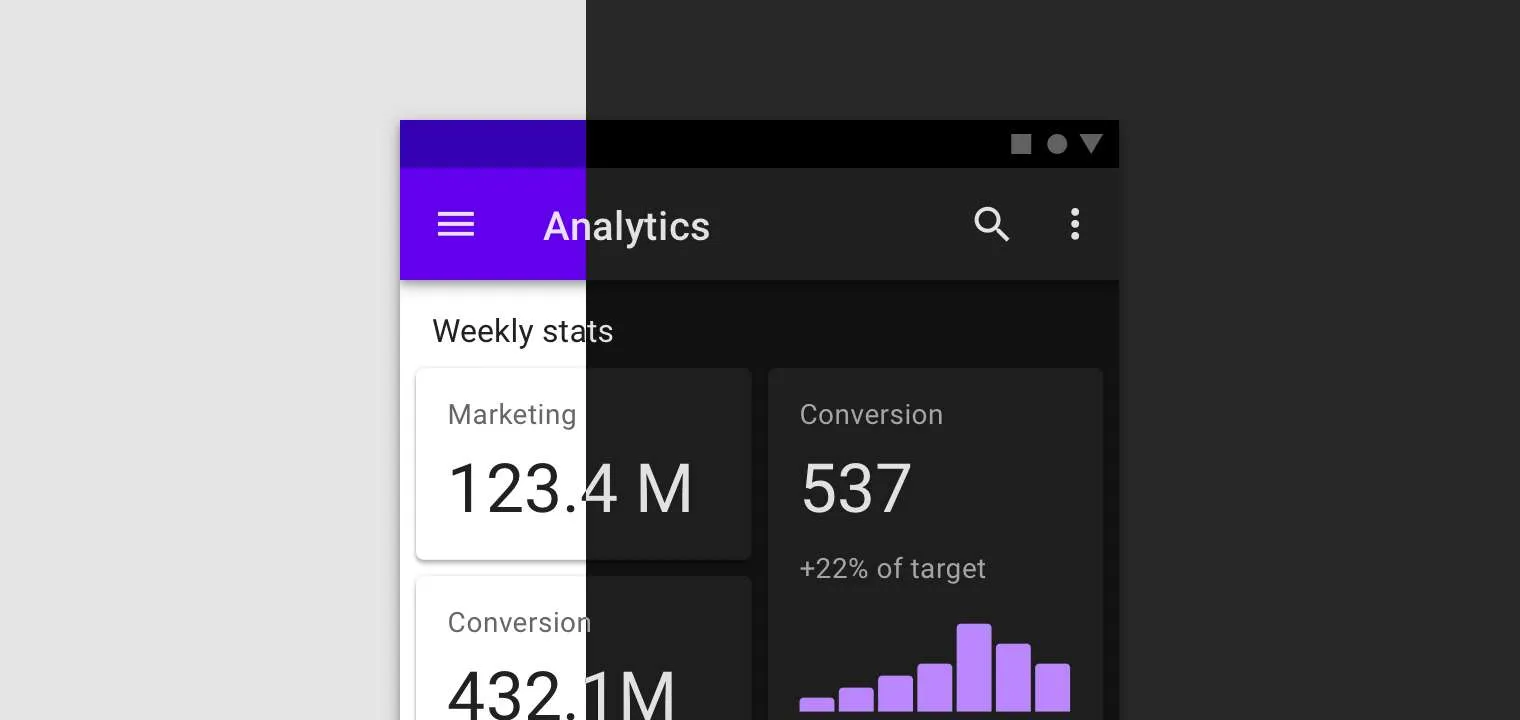

How to build design system with SwiftUI

Building a design system to support one product is not easy - it has to be robust and flexible at the same time for scalability. Though challenging, lots of great resources have shared useful principles and approaches that help teams build a good system both visually and programmatically. Standing on their shoulders, this article tries to contribute to an untouched ground by focusing on building a good system in SwiftUI.

Why do I write this article

During my first summer in ITP at New York, I’m lucky to have the opportunity to work as an iOS developer intern at Line Break Studio. One task I’ve been assigned to is building a design system in two steps: first visually in Sketch, and then programmatically in SwiftUI. The experience of experimenting with the new framework and building a design system with it has been amazing, but also buggy along the way. That’s why we’d like to share our experience with the community, hopefully making your development process easier.

What is SwiftUI

Apple released this groundbreaking new framework in WWDC 2019, which is one of the bests in years. From the point of view as a web developer, the project development experience in SwiftUI is closer to which in conventional front-end stack and frameworks.

This is definitely an awesome move because programming interface and managing states are drastically easier than before. And the best part of this improvement is that one can integrate UIKit and SwiftUI smoothly. To learn the basics of SwiftUI, the official tutorials provided by Apple are very helpful.

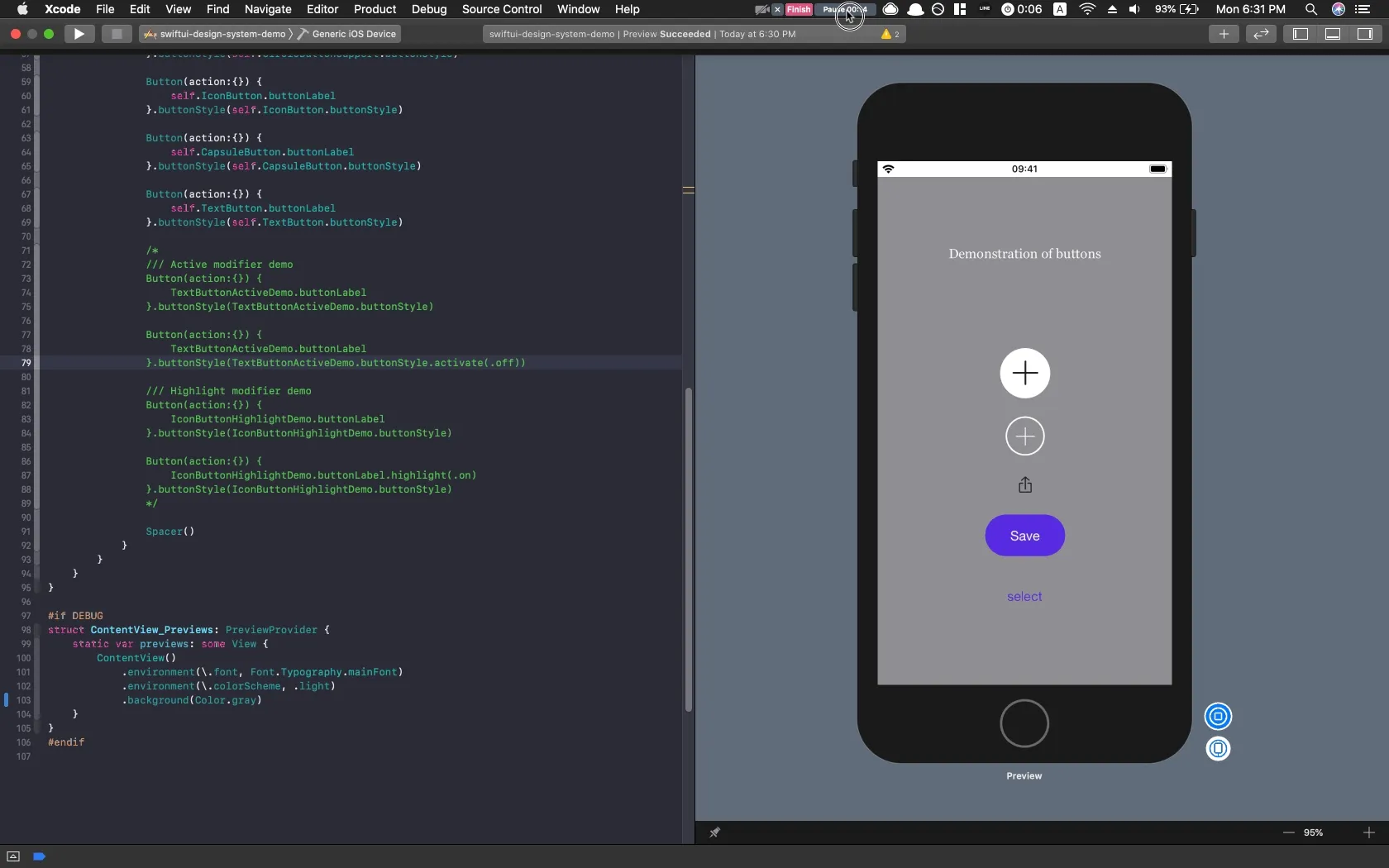

Demo project

For demonstration purpose, I put up a simplified version of design system we built in Line Break Studio. It a set of button components in different forms, which are built on top of two lower level parts: typography and colorPalette.

The project is public on GitHub, and I’m using Xcode 11 Beta 5 for development. An Airtable base as design system management hub (read more about workflow management) is also public for reference.

Principles of building design system

Design system in code is a middleware between designers and developers. Developer of the system takes inputs from design system in visual form, and produces API that’s identical with which for further development. Following two principles should be recognized to complete this system in code:

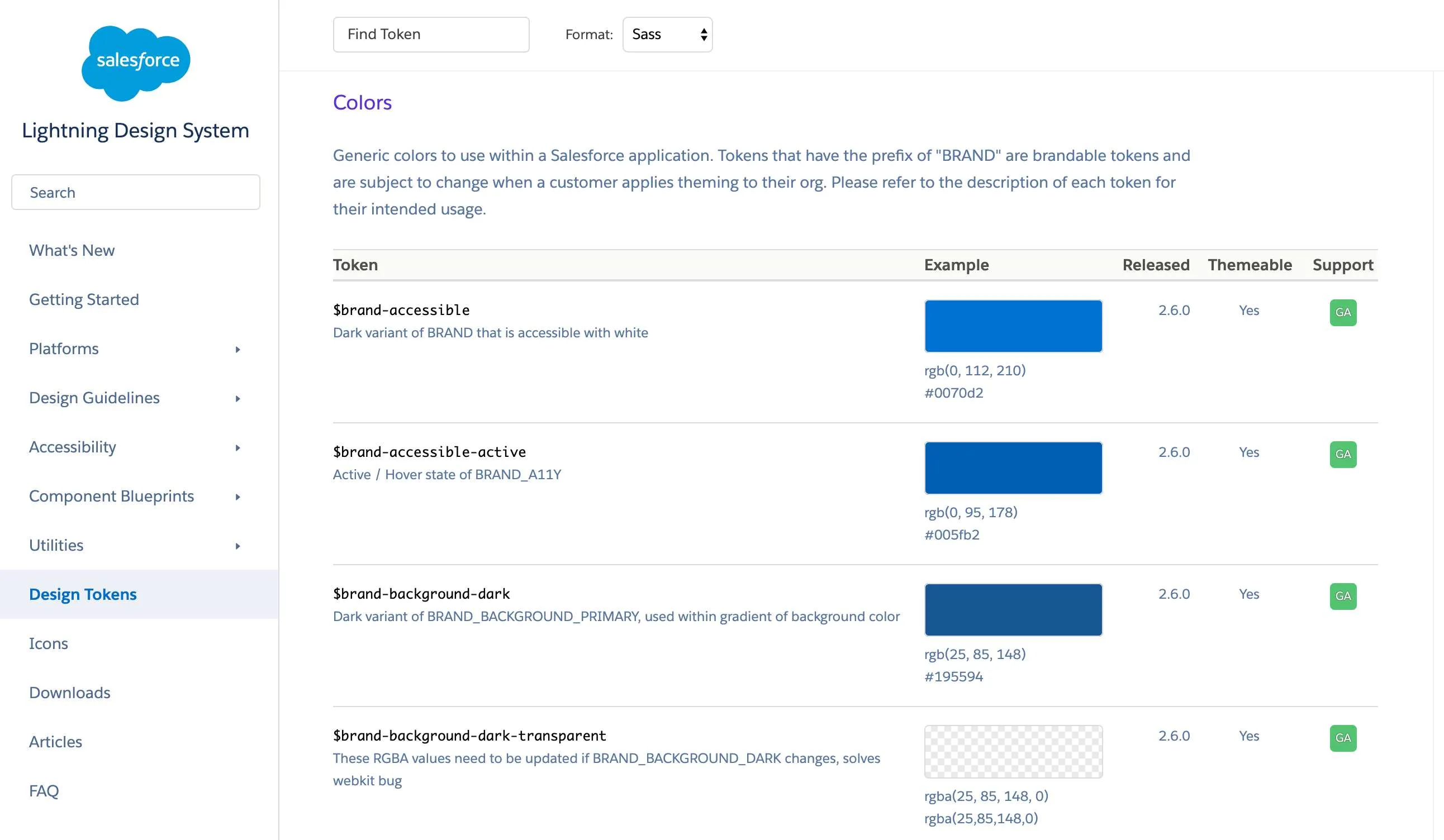

1. Communicate with tokens

Fundamentally, the purpose of having a design system in program is not about better code management or development efficiency, but to make sure the view is consistent with design files. To achieve that goal, using tokens to signify certain color, font, size or any visual elements is crucial to maintain quality of communication between developers, designers and managers in a team.

2. Levels of hierarchy

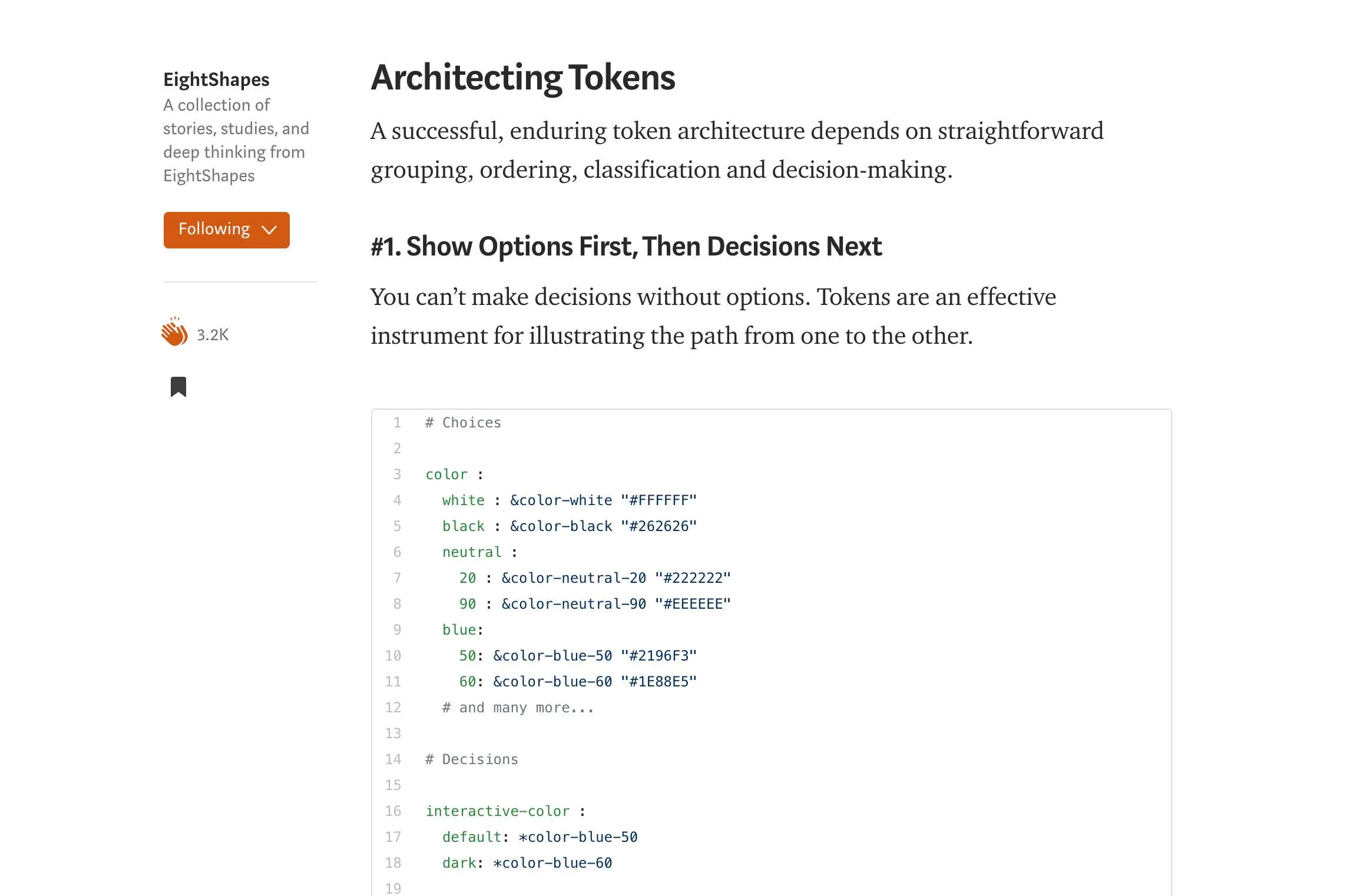

In EightShapes’ article, it points out that we should “Show options first, then decisions next”, because “You can’t make decisions without options.”

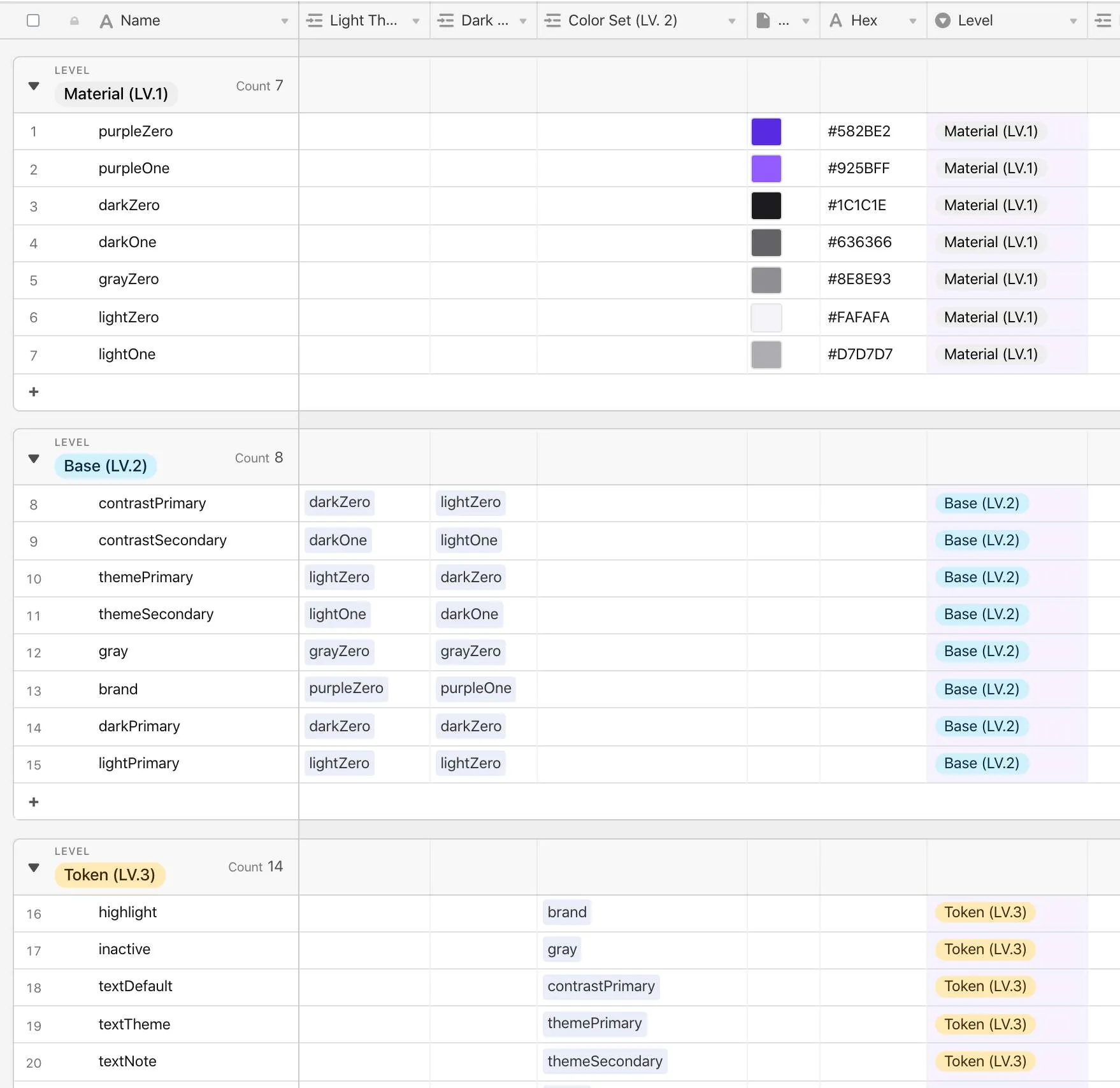

This kind of ordering architecture loosens the degree of coupling between different levels, hence providing more flexibility and dynamic for possible revisions. The way I structure the levels is in this order from bottom to top: material → base → token. But it could be anyway the team’s comfortable with.

Diving into code

Following section is a list of highlights we’d like to point out based on our experience. Please visit the GitHub repo for complete code. Any feedbacks or critics are welcome for improvements.

1. Architecting levels of hierarchy

There’re two ways of stacking materials at lower level to construct tokens at highest level:

- Use enum for type safety and code literacy

Advantages of using enum in code as grouping wrapper or parameter in function have already been well recognized. One point worths mentioning here is the implementation of levels of hierarchy.

We always store the raw values, including font size (CGFloat) and font name (String), at the lowest level, because we don’t want to mess around with it. But because raw value must be a literal in enum, we can’t just assign a case to be a value from the other enum.

To work around this problem, we implement a function getValue, which returns the raw value in switch case when necessary.

struct BaseColor {

/// dynamic color sets (with dark and light mode)

let contrastPrimary = Color("contrastPrimary")

let themePrimary = Color("themePrimary")

/// staic color sets (not updating along with color mode)

let darkPrimary = Color("darkPrimary")

let lightPrimary = Color("lightPrimary")

}

struct TokenColor {

let baseColor = BaseColor()

let textDefault: Color!

let textTheme: Color!

let textLight: Color!

let buttonTheme: Color!

let buttonContrast: Color!

let backgroundDefault: Color!

let backgroundTheme: Color!

init() {

/// themePrimary

self.textTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

self.buttonTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

self.backgroundTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

/// contrastPrimary

self.buttonContrast = baseColor.contrastPrimary

self.textDefault = baseColor.contrastPrimary

self.backgroundDefault = baseColor.contrastPrimary

/// lightPrimary

self.textLight = baseColor.lightPrimary

}

}

- Use struct for easier structure

Though enum is great, we don’t need its unique feature in some cases. For example, because Xcode takes care of the heavy job of processing dynamic colors, and no parameter options are required in API endpoint, we can set up color palettes by a simple two levels of struct.

struct BaseColor {

/// dynamic color sets (with dark and light mode)

let contrastPrimary = Color("contrastPrimary")

let themePrimary = Color("themePrimary")

/// staic color sets (not updating along with color mode)

let darkPrimary = Color("darkPrimary")

let lightPrimary = Color("lightPrimary")

}

struct TokenColor {

let baseColor = BaseColor()

let textDefault: Color!

let textTheme: Color!

let textLight: Color!

let buttonTheme: Color!

let buttonContrast: Color!

let backgroundDefault: Color!

let backgroundTheme: Color!

init() {

/// themePrimary

self.textTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

self.buttonTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

self.backgroundTheme = baseColor.themePrimary

/// contrastPrimary

self.buttonContrast = baseColor.contrastPrimary

self.textDefault = baseColor.contrastPrimary

self.backgroundDefault = baseColor.contrastPrimary

/// lightPrimary

self.textLight = baseColor.lightPrimary

}

}

2. Clear and straightforward naming of API endpoint

Naming convention is another broad topic for discussion and debate. In addition to basic Swift conventions, the only two rules we abide are, 1) no acronym and 2) making it simple. For example, to use typography and color system, instead of creating new endpoints, we make extension from Font and Color structs. This approach decreases the effort to memorize unfamiliar API names for developers.

struct TokenColor {

// --skip--

// see here for more: https://gist.github.com/vince19972/70eee7d66735739aa31567efd7a0a475

}

struct TokenTypography {

// --skip--

// see here for more: https://gist.github.com/vince19972/8ff8635bdb7bfdf54b85ab711b55f634l

}

// extend from native `Color` and `Font` struct

extension Color {

static let Token = TokenColor()

}

extension Font {

static let Typography = TokenTypography()

}

// use the tokens

struct ContentView: View {

Text("Demo of extension")

.font(Font.Typography.mainFont)

.foregroundColor(Color.Token.textTheme)

}

3. Manage color sets dynamically in two modes

So dark mode has become a standard in industry, and both iOS and Android team have implemented this feature. It’s a good trend for users, but could bring designers and developers some challenges, including managing and naming the color sets, especially gray scale ones.

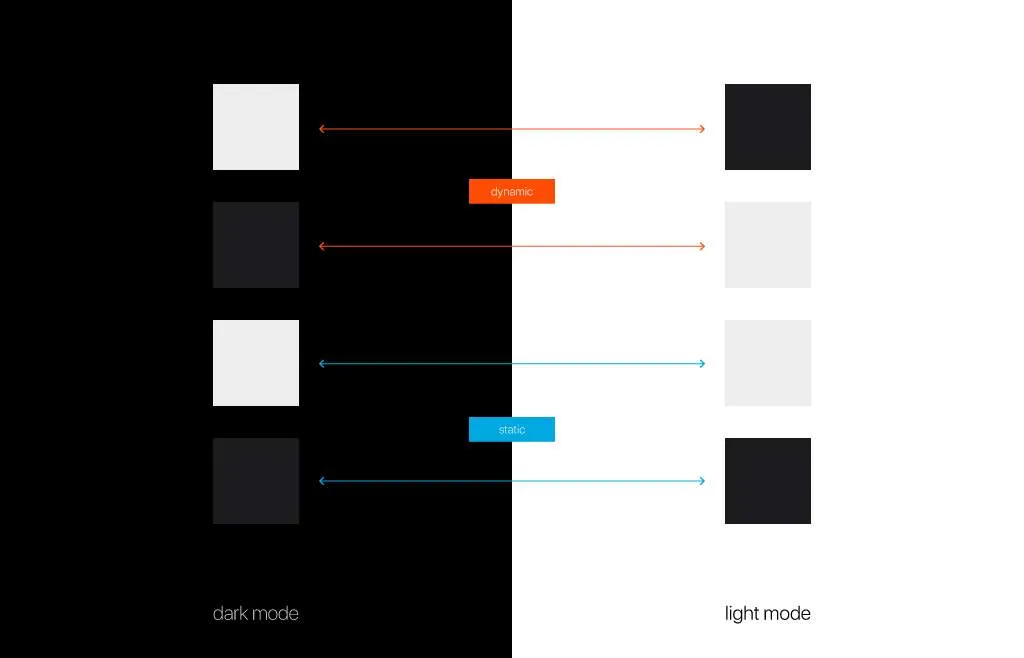

To think and communicate about gray scale colors dynamically, using terms like white, light, black or dark doesn’t work. Because if we referred to a dynamic color #000000 (black in HEX) black or dark in light color scheme, how do you talk about this particular color, which should turn into #FFFFFF (white in HEX), in dark color scheme? defaultDark or lightDark?

It is very confusing to name gray scale dynamic color sets in conventional approach. To avoid this confusion, we use theme and contrast to manage one set of color in light and dark schemes instead. Please see this table as reference:

Note that a gray scale color doesn’t always need to be reversed in opposite color mode. In these situations that light color remains light and dark remains dark, we simply name name it light or dark instead.

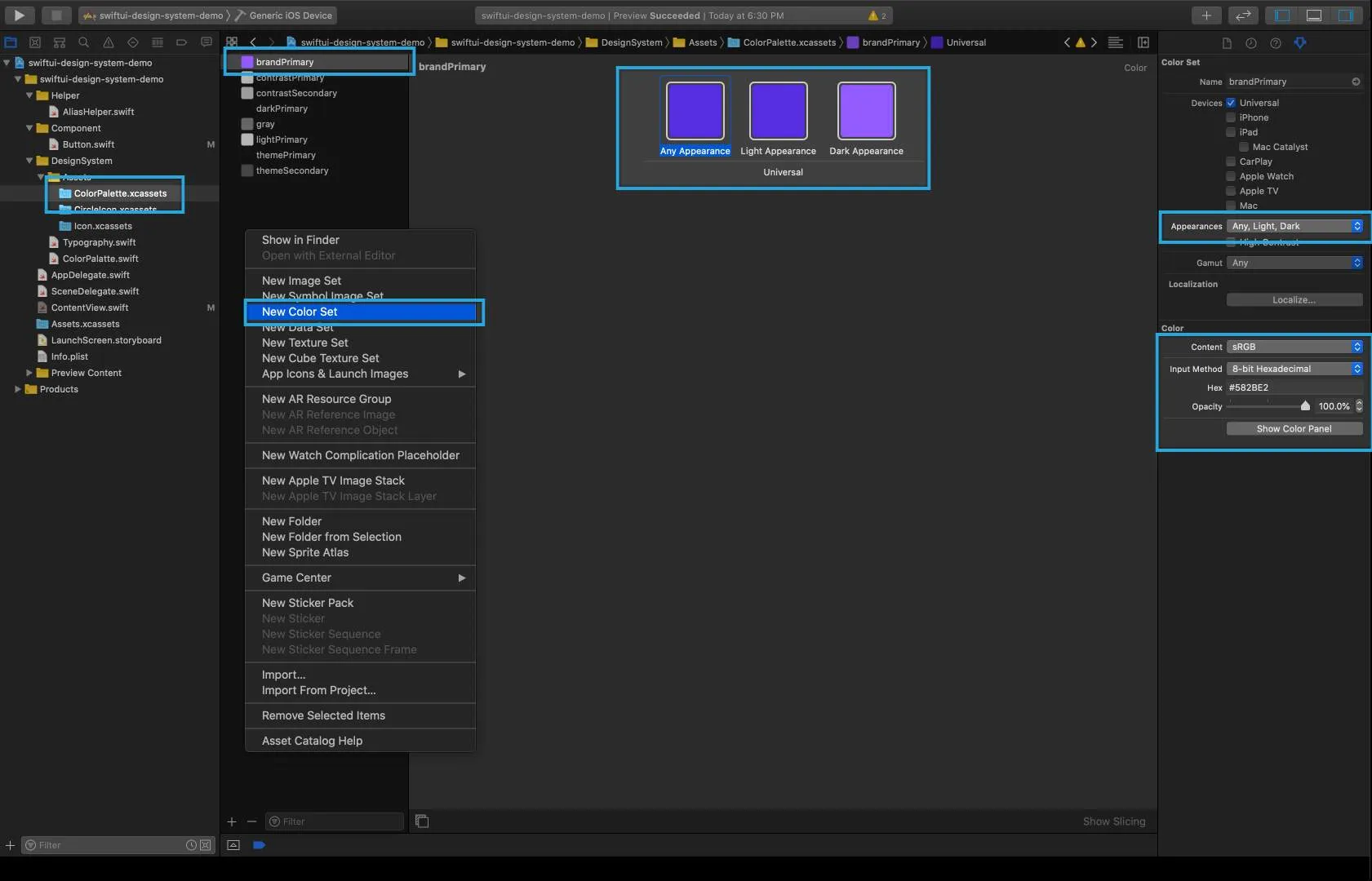

Once we wrap our head around this naming method, managing this architecture of color palette is easy in Xcode. To create a color set, simply create a new Asset Catalog file → add a new Color Set → and change Appearances to Any, Light, Dark will do.

4. environment settings

One awesome feature in SwiftUI framework is the environment modifier, which provides ability to control environment values on target view. In terms of building design system, this ability provides convenient approach to change app’s font at root level. And the other advantage of using environmentValue is to change and test light and dark color schemes in development.

#if DEBUG

struct ContentView_Previews: PreviewProvider {

static var previews: some View {

ContentView()

.environment(\.font, Font.Typography.mainFont)

.environment(\.colorScheme, .dark)

}

}

#endif

5. buttonStyle and button label

Comparing to the old days in UIKit, constructing reusable buttons in SwiftUI is drastically easier. The Button view consists of two parts, which are action closure (event to be fired as button is pressed) and label (body of the button). The view can then be chained with a modifier buttonStyle. To learn details about building reusable buttons,I recommend reading Alejandro’s tutorial, which is comprehensive and useful.

In our customized button components, first step is to create two structs, including TokenButtonLabel and TokenButtonStyle. These two structs are programmed according to the types of buttons we have in design files. For example, there’re only two types of labels: icon and text. Each type has an according init function designed with different parameters for new instances.

struct TokenButtonLabel: View {

/// Global properties

private let labelType: LabelTypes

private var iconName: String?

// Icon Type

private var iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize?

init(name: String, iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize) {

self.labelType = .icon

self.iconName = name

self.iconSize = iconSize

}

// Text Type

private var btnText: String?

init(text: String) {

self.labelType = .text

self.btnText = text

}

/// Helper function

func getView() -> some View {

var renderView: AnyView!

let highlightSuffix = isHighlighted ? "-highlight" : ""

switch labelType {

case .icon:

let iconString = "\(iconName!)\(highlightSuffix)"

renderView = AnyView(

Image("\(iconString)")

.resizable()

.aspectRatio(contentMode: .fill)

.frame(width: iconSize!.rawValue, height: iconSize!.rawValue, alignment: .center)

)

case .text:

renderView = AnyView(

Text("\(btnText!)")

.font(Font.Typography.sizingFont(font: .main, size: .body))

)

}

return renderView

}

// Rendering View

var body: some View {

getView()

}

}

On the other hand, there’re four major types of button styles: circle icon, icon, capsule and text. To follow ButtonStyle protocol, a makeBody func has to be implemented. This function brings us a configuration property, providing a native isPressed value to monitor if the button is pressed or not.

struct TokenButtonStyle: ButtonStyle {

/// Global properties

private let styleType: StyleType

private var iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize?

private var backgroundColor: Color?

private var borderStyle: StyleAlias.BorderStyle?

private var textColor: Color?

/// Circle Icon Button

init(iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize,

backgroundColor: BackgroundColor,

border: BorderStyle? = .none) {

// --skip--

}

/// Icon Button

init(iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize) {

// --skip--

}

/// Capsule Button

init(backgroundColor: BackgroundColor, textColor: TextColor) {

// --skip--

}

/// Text Button

init(textColor: TextColor) {

// --skip--

}

/// Rendering Button Style

func makeBody(configuration: Self.Configuration) -> some View {

var renderView: AnyView!

let verticalMargin = CapsuleValue.verticalMargin.rawValue

let horizontalMargin = CapsuleValue.horizontalMargin.rawValue

switch styleType {

case .circleIcon:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .icon:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .capsule:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .text:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

}

return renderView.opacity(getOpacityValue(configuration.isPressed))

}

}

Finally, stacking on top of TokenButtonLabel and TokenButtonStyle, the endpoint of the button component API will be TokenButton - a grouping that wraps content and style of button together, conforming to the button types in visual design system.

struct TokenButton {

var buttonLabel: TokenButtonLabel

var buttonStyle: TokenButtonStyle

// Circle Button

private var circleBtnType: CircleBtnType! = .primary

private var circleBtnIcon: String! = "circle-plus"

init(circleButtonType: CircleBtnType, buttonIcon: String) {

// --skip--

}

// Icon Button

private var iconBtnType: IconBtnType! = .action

private var iconBtnIcon: String! = "upload"

/// Icon Button

init(iconButtonType: IconBtnType = .tool, buttonIcon: String) {

// --skip--

}

// Capsule Button

private var capsuleBtnText: String! = "Save"

init(capsuleText: String) {

// --skip--

}

// Text Button

private var textBtnText: String! = "select"

init(buttonText: String) {

// --skip--

}

}

6. AnyView as wrapper

As we’re dealing with the makeBody function brought by ButtonStyle protocol, we found a useful tip to work with View. To store a view in a variable, the type annotation could be indicated as AnyView, which works as a general container of views in SwiftUI.

In our case, because we want to add the opacity modifier to configuration.label to all types of buttons, instead of doing so repeatedly in each switch case, it makes more sense to chain the modifier at the end altogether. We can achieve this pattern by using the advantage of AnyView in this way:

struct TokenButtonStyle: ButtonStyle {

/// Global properties

private let styleType: StyleType

private var iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize?

private var backgroundColor: Color?

private var borderStyle: StyleAlias.BorderStyle?

private var textColor: Color?

/// Circle Icon Button

init(iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize,

backgroundColor: BackgroundColor,

border: BorderStyle? = .none) {

// --skip--

}

/// Icon Button

init(iconSize: TokenButton.IconSize) {

// --skip--

}

/// Capsule Button

init(backgroundColor: BackgroundColor, textColor: TextColor) {

// --skip--

}

/// Text Button

init(textColor: TextColor) {

// --skip--

}

/// Rendering Button Style

func makeBody(configuration: Self.Configuration) -> some View {

var renderView: AnyView!

let verticalMargin = CapsuleValue.verticalMargin.rawValue

let horizontalMargin = CapsuleValue.horizontalMargin.rawValue

switch styleType {

case .circleIcon:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .icon:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .capsule:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

case .text:

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

// --skip--

)

}

return renderView.opacity(getOpacityValue(configuration.isPressed))

}

}

7. Build view modifier with mutating function

To update styles of the buttons dynamically, we can build our own modifier. First instantiate customized mutable state properties in view, and then create a mutating function which returns a Self type after updating the target state property.

// buttonLabel modifier

struct TokenButtonLabel: View {

// --skip--

/// State properties

var isHighlighted = false

// --skip--

}

extension TokenButtonLabel {

/// Pass highlightSwitch argument bonded with @State variable in order to trigger updates

mutating func highlight(_ highlightSwitch: TokenButton.StateSwitch) -> Self {

self.isHighlighted = highlightSwitch == .on ? true : false

return self

}

}

// buttonStyle modifier

struct TokenButtonStyle: ButtonStyle {

// --skip--

/// State properties

var isActive = true

// --skip--

}

extension TokenButtonStyle {

// Pass highlightSwitch argument bonded with @State variable in order to trigger updates

mutating func activate(_ activeSwitch: TokenButton.StateSwitch) -> Self {

self.isActive = activeSwitch == .on ? true : false

return self

}

}

8. Tricky border style

One drawback of SwiftUI is styling a circle shape with circular border is not straightforward at all. I struggled for a while, and finally found a solution here on StackOverflow. A clipShape and an overlay modifier are required to make it work.

// --skip--

renderView = AnyView(configuration.label

.background(backgroundColor!)

.frame(width: iconSize!.rawValue, height: iconSize!.rawValue, alignment: .center)

.clipShape(RoundedRectangle(cornerRadius: iconSize!.rawValue))

.overlay(RoundedRectangle(cornerRadius: iconSize!.rawValue)

.stroke(borderStyle!.color, lineWidth: borderStyle!.width))

)

// --skip--

Conclusion

SwiftUI is an incredible improvement Apple makes. Though flaws still exist, building a robust and flexible design system with it, and furthermore complicated UI in iOS is way efficient than ever. I hope this article is helpful for any iOS team trying to build UI, and always welcome to any feedbacks!

👉 This article is also published on freeCodeCamp and Dev.to